By ERIC JAFFE

I’m not a doctor, but I do sit near one in The Atlantic’s New York office. So you can trust me to know that MD-in-residence James Hamblin is on to something when he writes in the magazine’s October issue about the rising appreciationamong physicians for the health benefits of parks and green space. Hamblin writes of “a small but growing group of health-care professionals who are essentially medicalizing nature”:

At his office in Washington, D.C., Robert Zarr, a pediatrician, writes prescriptions for parks. He pulls out a prescription pad and scribbles instructions—which park his obese or diabetic or anxious or depressed patient should visit, on which days, and for how long—just as though he were prescribing medication.

Seems the medical community has finally caught up with insights made by the urban landscape community 150 years ago. In 1865, Frederick Law Olmsted of Central Park design fame called it “a scientific fact” that natural “is favorable to the health and vigor of men.” (And women!) Olmsted jumped the gun on the whole “fact” thing, but time and a whole bunch of modern behavioral researchon the nature-health link has proved him wise.

Exactly what makes parks and trees so healthy for people remains a matter of ongoing discussion. One credible theory, pioneered by Michigan psychologist Stephen Kaplan, holds that nature restores and refreshes our brains, much like sleep, because it doesn’t require direct attention. Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson has attributed the effects to “biophilia”—essentially, that humans are more comfortable in nature because that’s where they evolved.

Here’s Wilson chatting with The Washington Post a few weeks back:

“Instinctively, without understanding what’s happening, they know that in certain wild environments, they have come home,” Wilson said.

Connecting with nature is especially important for the world’s “increasingly urbanized population,” says Wilson. To that end, CityLab has compiled a nearly complete health case for more city green space. The lit review’s purpose is to show that urban nature is (as Olmsted might say) favorable to public health and psychological well-being, and also why it’s so critical for people who live in the high-stress city to occasionally (as Wilson might say) go home again.

Depression

There’s some pretty clear evidence that walking through nature puts people in a better mood than does walking through a city setting. That’s not a huge surprise given the stressful confines of crowded sidewalks. But the findings are especially significant considering the link between urbanization and mental illness, including depression.

A 2009 study found that a 15-minute stroll through the woods led participants to have more positive emotions—and to reflect on a life problem more constructively—than their counterparts who walked in an urban setting. A 2012 study even found nature-related mood gains in major depressive cases. Research published earlier this year found that Londoners living near street trees were prescribed fewer antidepressants.

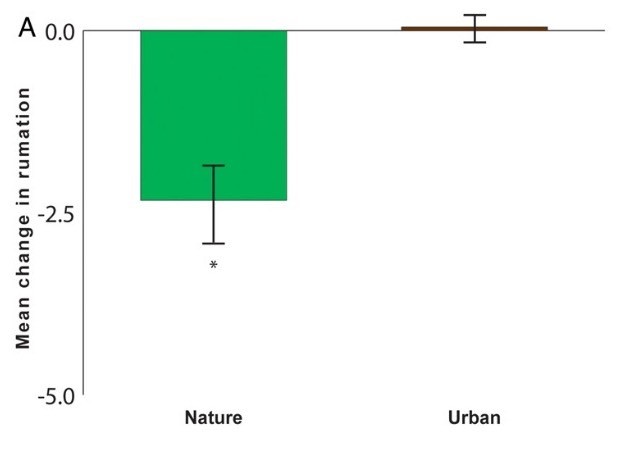

New work from Stanford’s Gregory Bratman, published this year in top journalPNAS, suggests that nature’s impact on harmful rumination might hold the key to its anti-depressive power. Participants who took a 90-minute nature walk reported having less rumination and showed decreased neural activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex—a part of the brain linked with sadness and self-reflection. The findings “suggest that feasible investments in access to natural environments could yield important benefits for the ‘mental capital’ of cities and nations.”

Happiness and well-being

On the flipside of the emotional spectrum, other work has linked proximity to urban parks with higher well-being. U.K.-based researchers surveyed about 10,000 Brits on how satisfied they were with their lives, as well as whether they had general signs of mental distress. In the journal Psychological Science, the researchers reported that having more green space nearby led to a clear spike in life satisfaction—“equivalent to 28% of the effect of being married rather than unmarried and 21% of being employed rather than unemployed.” They conclude:

Our analyses suggest that individuals are happier when living in urban areas with greater amounts of green space.

General health and mortality

Generally speaking, people who live near urban green space do an admirable job not dying. Past research has found clear associations between city nature and reduced morality for many different causes of death. A new meta-analysisreviewed a number of previous studies and found “strong evidence” linking the quantity of residential green space with all-cause mortality and “moderate evidence” linking it with perceived general health.

Another 2015 paper, this one published in Scientific Reports, put the health benefits in starker terms. After studying general health and tree density in Toronto (while controlling for other demographic factors), the researchers found that having 10 more trees on a city block improved perceived health on par with being seven years younger or $10,000 a year richer. Money may not grow on trees, but the keys to a healthier life just might.

Stress

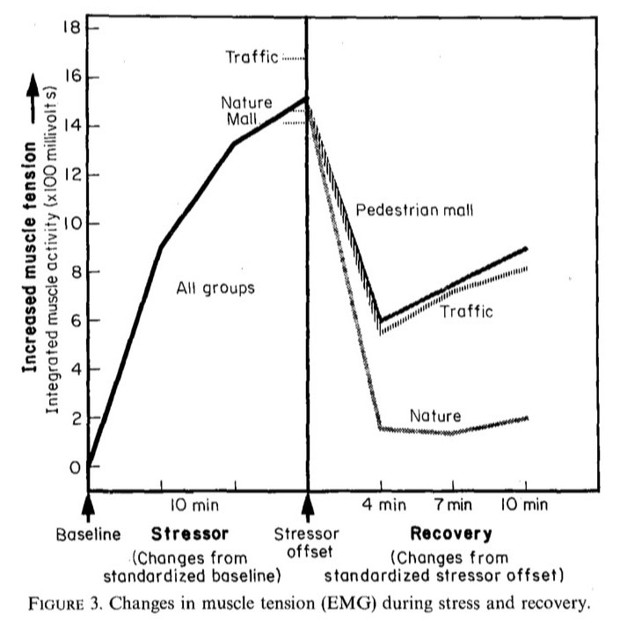

Environmental research legend Roger Ulrich and collaborators captured the stress-relieving qualities of nature in a clever study from 1991. They gathered 120 test participants into the lab, stressed them out with clips from a work accident film called “It Didn’t Have to Happen,” then showed them videos of various environments. Some participants saw a video of a city pedestrian shopping mall, others watched urban traffic, and others looked at nature.

On four different physiological stress measures, including muscle tension, participants in the nature group recovered more quickly and completely than did those shown the urban environments. Ulrich et al conclude in the Journal of Environmental Psychology:

The findings strongly suggest that environments of importance to well-being and stress are not confined to settings having extreme or unusual properties, such as loud noise or extreme temperatures, but also include very common environments that most urbanites in developed nations encounter daily.

Subsequent research reached similar conclusions outside the lab. A 2003 study, conducted in nine Swedish cities, found that people who visited urban green spaces more often reported less stress-related illnesses.

Attention

In more recent years, a lot of research has focused on how urban nature helps people … focus.

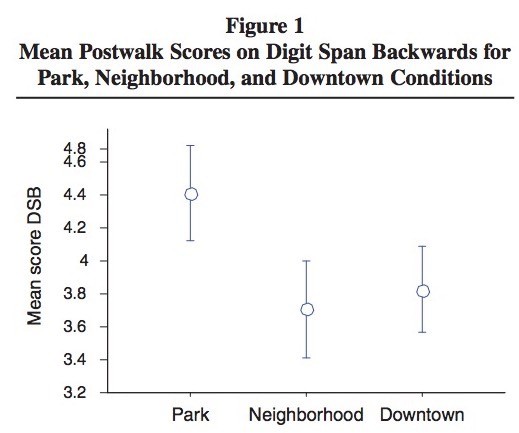

A highly cited study by Marc Berman, John Jonides, and Stephen Kaplan gave some test participants a tough attention-related task that involved remembering numbers. Thus cognitively spent, some participants then took a walk through the famed Nichols Arboretum in Ann Arbor, Michigan, while others walked through the downtown area. When the participants returned to the lab and took the test again, the refreshed nature group scored significantly higher, the researchers reported in a 2008 issue of Psychological Science.

Other work is mixed on just how ensconced in leaves you need to be to get the cognitive boost. A study from 2012 found that the denser a park’s vegetation—meaning, less sight of the city through the trees—the better. But other work has found attention benefits from a mere 40-second micro-glimpse of a green roof, or even looking up from your screen to see a desk plant.

Child attention

Even tots get a mental bump from grass and bark. In a 2009 study, kids aged 7 to 12 with diagnosed attention-deficit disorder showed better concentration after a 20-minute walk in the park, compared with children who walked downtown or in a neighborhood. “‘Doses of nature’ might serve as a safe, inexpensive, widely accessible new tool in the tool kit for managing ADHD symptoms,” the researchers concluded in a 2009 issue of the Journal of Attention Disorders. More recent work extended the cognitive benefits of urban nature to children without ADHD, too.

Aggression and restraint

The power of nature seems capable at times of transcending particular vulnerable environments. In a 2001 study, Illinois scholars Frances Kuo and William Sullivan found reduced levels of aggression in Chicago public housing residents whose view overlooked some trees, compared with others in the same complex who looked onto an empty common area. Kuo and Sullivan report in the journal Environment and Behavior that the additional mental fatigue that comes with not having visual access to nature might play a role in the diverging outcomes.

A study by Kuo and Sullivan as well as Andrea Faber Taylor, published thefollowing year in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, extended that research to discipline among girls in the same housing complex. Young women with tree views performed better on tests of concentration, delayed gratification, and inhibited impulsivity compared to those with barren views. “Perhaps when housing managers and city officials decide to cut budgets for landscaping in inner city areas, they deprive children of more than just an attractive view,” the researchers concluded.

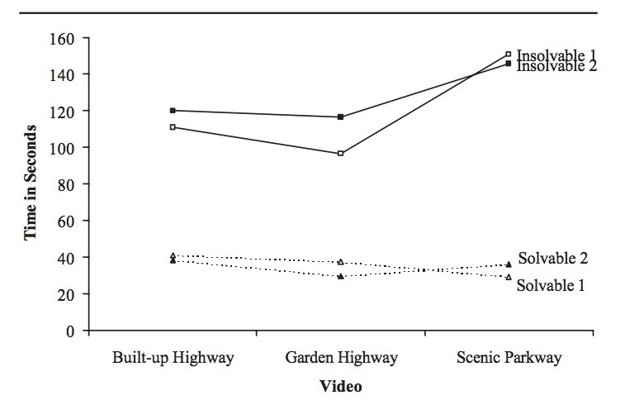

Other work has found reduced levels of road rage among test participants who watched videos of a drive along roads lined with and without nature. In a 2003 study, some participants watched the car cruise along a normal asphalt highway, others saw a little bit of greenery in a garden highway, and a third group saw dense vegetation in a scenic parkway. Afterward they all tried their hand at an anagram that, unbeknownst to them, was impossible (e.g. DATGI—eyes back on the road, please!); those who’d observed the scenic drive showed less impatience, working on the puzzle for 90 more seconds before giving up.

Post-operative recovery

If you’re in a hospital, the last thing you’re really worried about is the view. But having a window that looks onto trees has been shown to have a measurable difference in patient outcomes. In a classic study published in Science in 1984, Roger Ulrich found that gallbladder surgery patients whose hospital rooms overlooked nature had “shorter postoperative hospital stays, received fewer negative evaluative comments in nurses' notes, and took fewer potent analgesics” than those whose windows faced a brick wall.

And these days, if the medical trend noted by James Hamblin catches on, you just might be prescribed a walk in the park on your way out.